Scleroderma’s Oral Spectrum: Small Mouths, Big Problems. A Case Series

CR4

Dr Mayson Mustafa

Dr F Mattan, Dr J H Macken, Dr M Mustafa, Dr J Buchanan, Professor F Fortune.

Abstract title:

Scleroderma’s Oral Spectrum: Small Mouths, Big Problems. A Case Series.

Authors: Dr F Mattan1*, Dr J H Macken1,2*, Dr J Buchanan1, Professor F Fortune1,2,3

Author affiliations:

1Oral Medicine department, Royal London Dental Hospital, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, E1 1BB.

2Oral Immunobiology & Regenerative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, 4 Newark Street, E1 2AT.

3London Behcet’s Centre of Excellence, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, E1 1BB.

*both authors contributed equally to this work.

Background:

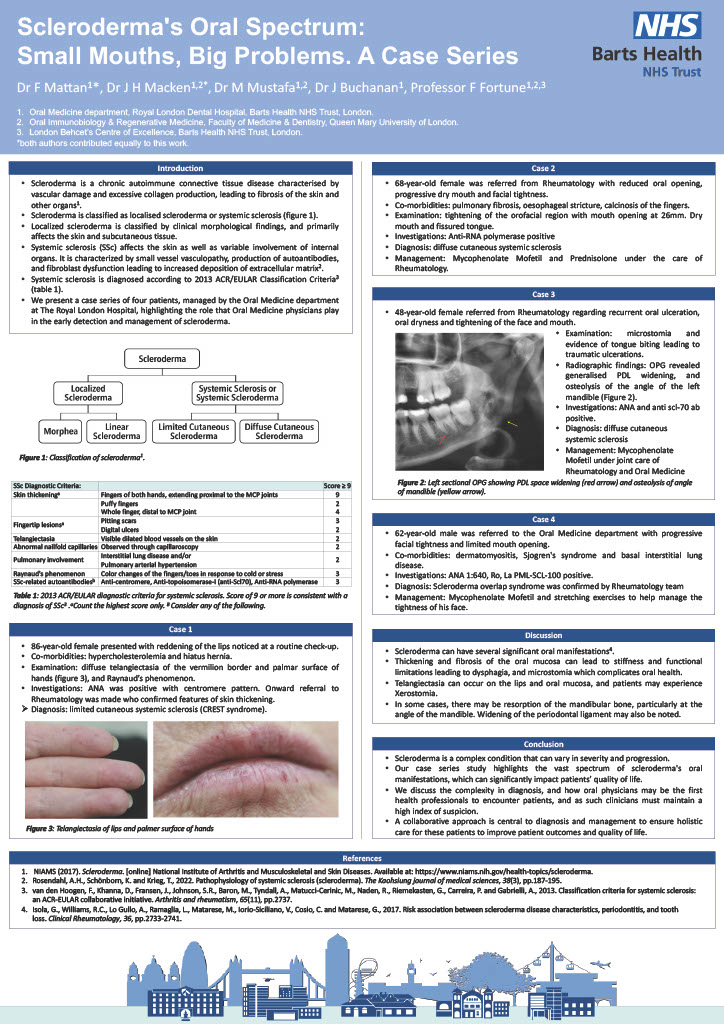

Scleroderma is a chronic autoimmune connective tissue disease characterised by vascular damage and excessive collagen production, leading to fibrosis. Scleroderma is typically classified Localized Scleroderma and Systemic Sclerosis. We present a case series of four patients, who presented to the Oral Medicine department at The Royal London Hospital, highlighting the role that Oral Medicine physicians play in the early detection and management of Scleroderma.

Case series:

Case 1: A 86-year-old female was referred by her dentist with reddening of the lips. Clinical investigation revealed diffuse telangiectasia of the vermilion border of labial mucosa, palate, face and palmar surface of hands, as well as raynaud’s phenomenon. ANA was positive with centromere pattern, confirming the diagnosis of limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (CREST syndrome).

Case 2: A 68 year-old female presented with reduced oral opening, progressive dry mouth and facial tightness. On examination, there was tightening of the orofacial region with mouth opening measured at 26mm, and saliva was frothy with reduced flow. She was diagnosed with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis, and managed with Mycophenolate Mofetil and Prednisolone.

Case 3 : A 48 year old female was referred from Rheumatology regarding recurrent oral ulceration and oral dryness. On examination, there was microstomia and evidence of periodontal disease. OPG radiograph revealed generalised PDL widening, and osteolysis of the angle of the left mandible. ANA and anti scl-70 ab were positive, consistent with a diagnosis of diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis and commenced on Mycophenolate.

Case 4: A 62-year-old male was referred to the Oral Medicine department with progressive facial tightness and limited mouth opening, and a history of dermatomyositis, sjogren’s syndrome and basal interstitial lung disease. With findings of ANA 1:640, Ro, La PML-SCL-100 positive, a diagnosis of Scleroderma overlap syndrome was confirmed.

Conclusion:

Scleroderma is a complex condition that can vary in severity and progression. Our case series study highlights the vast spectrum of scleroderma’s oral manifestations, which can significantly impact patients quality of life. We discuss the complexity in diagnosis, and how oral physicians may be the first health professionals to encounter patients, and as such clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion. A collaborative approach is central to diagnosis and management to ensure holistic care for these patients to improve patient outcomes.